In Yoruba societies, Balogun is an important chieftain. A war general with a battalion at his disposal. It was typical of them to live on the fringes, away from town centres close to borders. You would also expect the Balogun to be a man of few words–expectedly more skilled in warfare than in small talk. Perhaps gifted in those kinds of speeches that make soldiers on duty tour choose patriotic martyrdom.

Respected critic Biodun Jeyifo once characterised one of Nigeria’s finest writers, the late Kiagbodo poet John Pepper Clark, Balogun Otolorin. His reference was spurred in retrospect by JP Clark’s creative choices. I have already clarified who a Balogun is; in plain English, Otolorin is someone who walks alone or works differently.

Few contemporary musicians have successfully navigated the less-travelled path like Kizz Daniel. The vampiric music business ensures that talents answer to the money. Money is, of course, a synecdoche for record executives with superhero-level power and control such that they can swat a talent like a wasp and, in the same breath, gulp from a glass of lemonade.

Kiss Daniel trod the less-travelled path and emerged almost unscathed if you ignore the slight change to how his moniker is spelt — Kizz Daniel. That success has meant one thing. He has excelled where most of his peers have failed. His most recent LP album is called Maverick, which means unconventional or independently minded.

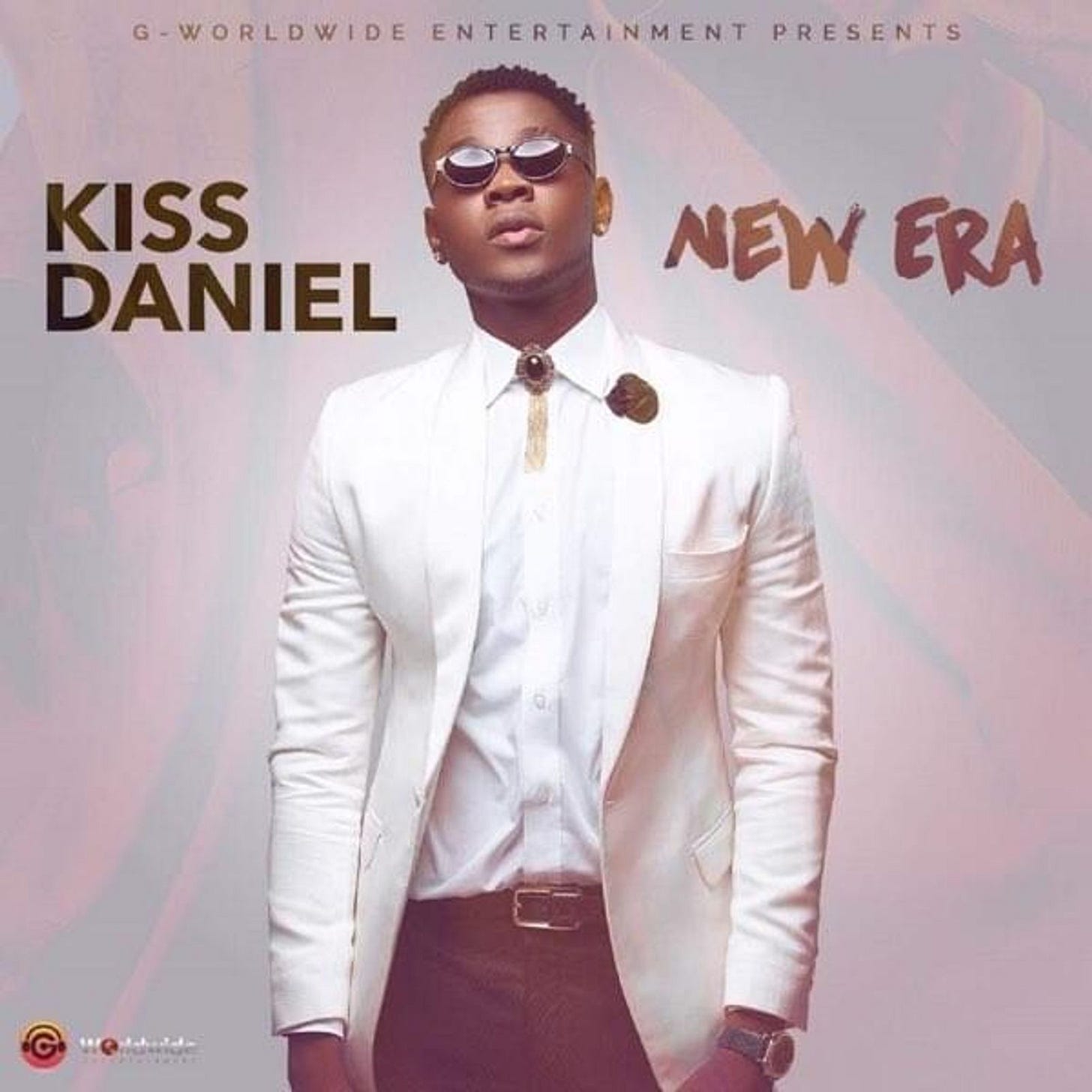

It has been nine years since the fully formed Tobiloba Anidugbe emerged on the musicscape with his hit-studded debut album, New Era. From its boisterous opening track, ‘New King’ full of rhetorical questions—Who the new king? Who is a king to you?—to the four-letter word titled love songs turned wedding standards (‘Laye’, ‘Woju’ and ‘Mama’) to self-deprecatory ‘Gobe’ to the dancefloor magnet ‘Good Time’ once covered by industry senior Wizkid, New Era holds up quite well in Kizz Daniel’s discography and the Afrobeats landscape.

In 2016, Headies awarded New Era the album of the year. Superstar, although nominated for Album of the Year in 2012, lost to P-Square’s Invasion. It would seem like I am peeling lemons for Wizkid FC, but comparing the career trajectories of Wizkid and Kizz Daniel is only a part of establishing Kizz Daniel’s maverick odyssey.

Kizz Daniel is hardly mentioned in discussions about the Big 3 or Big 5 Afrobeats superstars that have dominated music discourse. This partly makes sense, as he has always remained independent. The kind of budget that pushes a musician into the mainstream of proper Afrobeats requires that the musician be a puppet on a string. It is clear that leaving the stables of G-Worldwide taught the Abeokuta native at least one thing: He could fly his own career.

When Kizz Daniel scored his first hit, ‘Woju’, in 2014, our music landscape was very different from where it is now. Sean Tizzle, poised for stardom, had just released his smash album, The Journey. Wizkid had also released his elusive sophomore album, Ayo, his last with the Banky W-run EME, but this mixed-bag album was only a prelude to the packet of singles and the most energetic feature run in Afrobeats lore. That year, Olamide’s third album, Baddest Guy Ever Liveth, clinched Headies' coveted Album of the Year award. Burna Boy was one LP album deep; his beeline to superstardom was more imagined than real. In 2014, Kizz Daniel was where Kunmie, popular for ‘Arike’, is now in 2025: He had a big hit song, and the world was waiting for his next song.

Kizz Daniel replicated his hit formula with ‘Laye’, which was initially dismissed as inferior to ‘Woju’. There were clear similarities. In retrospect, it was a matter of personal style, not an attempt at a knockoff. With time, ‘Laye’ has been vindicated as the superior song—ask Afrobeats DJs who play at weddings. ‘Laye’ is layered with emotive lyrical repetitions; there is a humorous play on enunciating English words with a Yoruba temperament/tongue. The music is earthy, comfortable in its own skin, rid of anxieties like foreign accent, international acceptance and urbane sleekness.

Another iconic album appeared two months after New Era was released: Adekunle Gold’s debut, Gold. In retrospect, Gold is a rare gem in Afrobeats discography. A folksy album drenched in Yoruba popular music ethos, Adekunle Gold’s approach to the loverboy persona was something out of Yoruba Nollywood movies. The slight young man sported a punk afro and loved adire fabrics. In the music video of his duet with his future wife, Simi, ‘No Forget,’ he plays the impoverished bachelor tongue-lashed by his future mother-in-law, played by the iconic actor Ayo Mogaji.

Like Kizz Daniel, Adekunle Gold was also finding himself on Gold. He had arrived at a comfortable spot, revising traditional music with modern elements, but his ethos privileged tradition over modernity. Two albums later, Adekunle Gold would do up his persona in a trick that would impress Houdini. He became AG Baby, his nickname for his buffed avatar, and his lyrical style flipped from folksy to urbane cool.

His contemporary, Kizz Daniel, doubled down on his victories to cater to the Yoruba party, lately known as Owambe. Despite his record label troubles, he released a cache of exceptional songs that presented the familiar with zest and fun. Melodious ‘Yeba’ took a different approach to songwriting. Close to stream-of-consciousness and closer to character head-hopping, the song is set on a dance floor. The point of view kept changing. One second, someone is singing about being in love. Next, an irritated woman says, ‘Uncle, stop touching.’ A gentleman apologises. Then, the resounding mirth-drenched chorus goes on and on.

While Sean Tizzle, Kizz Daniel and Adekunle Gold were steeped in a Yoruba-centric approach to their music, another kind of sound was emerging on the soundscape. It was called Pon Pon (a less onomatopoeic name African Dancehall Music has been suggested), a sound heavily influenced by Ghanaian highlife music, which may have been brought into Afrobeats consciousness by Mr Eazi’s Juls-produced 'Skin Tight' (released in 2015). Pon Pon featured the pairing of relentless piano-produced synths with percussion, similar to the way the bass guitar and percussion are intertwined in palmwine highlife music. By 2017, Runtown’s ‘Mad Over You’, Tekno’s ‘Pana’ and Davido’s pair of hits ‘If’ and ‘Fall’ were the biggest Pon Pon hits.

Sean Tizzle has experienced a significant mid-career slump (the music is good, but people are not paying attention!). Adekunle Gold has become trapped in a tendency of his own making: an obsession with metamorphosis (the last time I checked, he morphed into a Mexican liquor). Meanwhile, Kizz Daniel has doubled down on his traditional approach to making music, similar to the processes of palmwine music.

He continued to hit the sweet spot of a rollicking, low-tempo, juju-infused Afrobeats. On his 2018 sophomore album, ‘No Bad Songz’, an early single, ‘No Do’, interpolates the theme song of Nigeria Television Authority’s children's programme, ‘Tales by Moonlight.’ Kizz Daniel may not have been an overt practitioner of Pon Pon, but his music shared a similar aesthetic: a West African one, where any musical instrument can be transformed into a drum. In highlife, juju, and most palmwine-derived music, the guitar is used in a manner similar to a drum. In most cases, it becomes a backing drum. The bass guitar entered juju music in the 1960s to replace the bass drum. If you listen closely to the Pon Pon sound, the relentless soft synth is, in fact, percussion adjacent.

In this way, you can draw a line from 1940s Juju pioneer Ojoge Daniel to Kizz Daniel. What is striking is that the thematic concerns of the music have remained largely unchanged. Take the preoccupation with women in Ojoge Daniel's ‘Obinrin Odale.’ His misogyny is illustrated quite clearly in how mistrustful a lover becomes when money becomes a problem. Kizz Daniel's ‘Fvck You’ body-count shames a lover rather than address the heartbreak, which is at the heart of the song. It is, in fact, revenge porn executed in song. But Kizz Daniel is also capable of peaches.

The great music critic Greil Marcus once wrote that “the very best pop music demonstrates a real absorption of events, political as well as personal”, even if Kizz Daniel’s interest is clearly skewed towards the personal, like his peers in the business of making contemporary dance music, he seems to gesture towards the political stance (or lack thereof) of his forbears in Yoruba music. In all his media appearances, when he embarked on a world tour with juju, King Sunny Ade insisted that his music preached peace and love. Kizz Daniel’s emphasis is on the latter. In fact, his third album, ironically titled King of Love (2020), was a political statement; it doubled down on his misogyny.

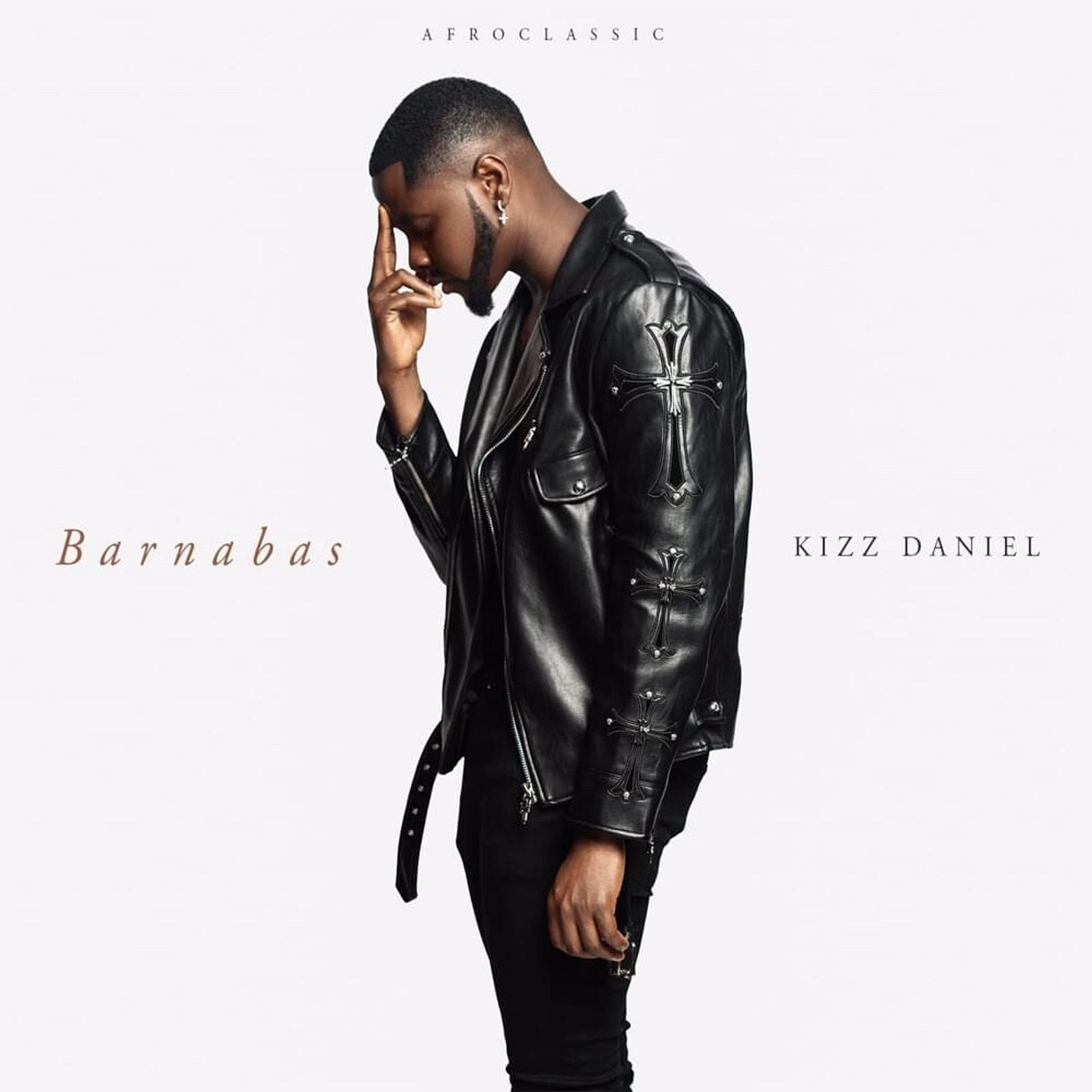

2021 brought us the redemptive Barnabas EP. Seven songs and twenty-one minutes long, this record explored themes of all shades of love (brotherly love, paternalistic love, and sensual love). Although it was an extended play project, it had the impact of a pitch-perfect full-length album. The production value was consistent and cohesive. It featured some fine bass guitar work, particularly on the Cavemen-assisted ‘Oshe’; you could find that Kizz Daniel was uber comfortable in his sonic range.

The rollout of promotional singles in the lead-up to his recent classic LP, Maverick, shattered the ceiling for Kizz Daniel. It contains two of his biggest hits, ‘Cough (Odo)’ and ‘Buga (Lo Lo Lo)’. His choice of music was also slightly altered. His newer songs featured the talking drum. On his recent classic ‘Twe Twe’ harmony is created when the talking drum is backed by a sound reminiscent of the steel pedal guitar. This clever production work advances the formal structure within juju/palmwine music.

His lyrical concerns have only changed slightly. You can draw a straight line from Kizz Daniel’s ‘Mama’ to Baby Shark-inspired ‘Double’. The elusive Mama he was trying to pick up on ‘Mama’ chose a blissful marriage with him to become the Mama of his kids on ‘Double’.

On ‘Black Girl Magic’, the opening song of his latest EP, Uncle K: Lemon Chase, his first verse relays a seemingly light conversation about choosing a life partner in a reported call and response,

“I tell my padi make he come see my baby

He say, “Ọrọbọ lo gbe”

No be body I dey find in a lady now

Ah, were ma leleyi!”

This kind of forward-thinking songwriting blends humorous quips, slang-laden dialogue, fraternal roasting, and men standing by their choices, insisting on the magic that Black women wield, as charming as it is tongue-in-cheek. As long as his pickup is not ‘Kanayo’, he feels safe. What does Kanayo signify? Could he be referring to the dodgy Nollywood character Kanayo O Kanayo? Or does Kanayo mean something different on the streets? Knowing Kizz Daniel’s middle-class upbringing, one may assume that his songwriting occasionally gestures towards the obscure. I am not sure that Vaddicts are clear on what he meant on the title track of Barnabas when he said, “Eni to mo way se boun lomo Barnabas.”

These details are ambiguous, but other aspects are relatively clear: ‘Black Girl Magic’ is a sex, gender, and body-positive song about Black girls, primarily from a male perspective. Agency here lies with the stand-up guy, Kizz Daniel’s stand-in, who does not look for “ body in a lady”. What about making a body-positive song that has nothing to do with a man’s gaze?

This may be a big ask, given that Kizz Daniel’s discography spots several problematic songs. Last year, he released ‘Thankz Alot’, a surprise four-track EP featuring the smooth ‘Showa’. It is a doting love song that checks in with a lover until the problematic part of the chorus,

“...Can you wake up around 4:30 (Sho wa?)

To make breakfast for me (Sho wa?)

To ba da lẹ, shole gimme gimme? (Sho wa?)

Gimme gimme ko ma gbomi jigi (Sho wa?)”

It is his tongue-in-cheek endorsement of a viral Tweet from a housewife who owned Nigerian Twitter with her devotion to making her husband’s meals. A strong online community of sophisticated, progressive X users (I believe the former word is 'woke') eschewing traditional gender roles for equitable, modern relationships were her target. The simple housewife doubled down on her celebration of traditional roles following several brand endorsements from the Telecommunications and Food and Beverage industries to the chagrin of Nigerian feminists.

One could attempt to date the beginning of Kizz Daniel’s Uncle K era to this song, but I suspect he has been around for longer. Remember ‘Yeba’? The “Uncle, stop touching” moment? The severe backlash occasioned on then Twitter? If you scour the internet, you may still find some think pieces about this moment, which, in its ambiguity, was co-opted by those who had a lot to say about frotteurism, particularly on dance floors.

Fola is the name every Afrobeats musician wants to share a marquee with. Clearly, on the ascent, Fola’s slim body of work suggests that he is a love child of a maternal Afro-Adura and a yet-to-be-determined father. His bromance with Kizz Daniel means that before the wax on ‘Lost’ dried, they blessed us with ‘Titi’, an unusual love song with a hook that borrows melodies from Africa China’s ‘Mr President.’ Kizz Daniel brings Machiavellian philosophy as it pertains to street love,

“Oloso wey forget to collect money don steal

Ọmọ wey no fight when you don cheat don kill...”

Then he doubles down on traditional roles again with popular Yoruba saying, “Ọlọbẹ ma lo lọkọ.” This may explain why he is popular with Nigerian parents; his gestures towards traditional music and values.

Not only Kizz Daniel struggles with notions of modernity and vulnerability. On the ‘Al-Jannah’, ODUMODUBLVK struggles to address his father’s terminal cancer and his mother’s miscarriages. He did not sound as confident as when he describes violent acts against men or stealthing female sexual partners. The charming Bella Shmurda comes through with a tribute for Mohbad, whose remains remain at the morgue, held to ransom by his own father, who is no longer mourning.

As if we don't have enough songs about Friday nights, Kizz Daniel teases a broke man with the extravagance of Friday night spending on ‘Secure’. The song itself is unadorned save for Zlatan’s rap verse and the backing talking drum.

The song ‘Police’ opens like Fela’s 1970s hit ‘Roforoforo fight’, then choral harmonies are stacked, reminiscent of South African gospel music, embellishing the chorus. West African Music matriarch Angelique Kidjo’s presence legitimises the interpolation of melodies and lyrics from her 90s hit ‘Agolo’. Johnny Drille’s presence lends the song a modern highlife legitimacy, facilitating a transnational conversation that spans both countries and decades. It is a propulsive, retro Afropop song that wears all its echoes from Fela to Kidjo. The song addresses Abena, an Akan name (Ghanaian) for a female child born on a Tuesday. Ghanaian words like Abena, Odoyewu, and Waakje have continued to thrive in Nigerian Afrobeats as vestiges of the Pon Pon era.

Runtown is featured on ‘Peace I Chose’, a song about a toxic relationship that avoids devolving into ambiguity or misogyny. The Reward Beatz-produced ‘Eyo’ sounds faintly like Asake’s ‘Uh Yeah’. The Adamu Orisha, emblematic of Lagos cultural life, is a rite of passage for any Yoruba musician. Now, you can safely say that both King Sunny Ade and Kizz Daniel have a song about Eyo, and you will be right!

In an industry where change is constant, Kizz Daniel has stuck to making lemonade from the lemons he knows how to handle. Whilst others court international exposure and adapt their style to fit the prevailing trends, Kizz Daniel has been the Balogun Otolorin of Afrobeats. In his music universe, Yoruba music is King, and he is a loyal subject. When he strays across national borders, you may find him in Benin Republic crate-digging from Angelique Kidjo. In a sense, Uncle K signifies a symbolic, if not mathematical, expression, where K stands for constant.

Insightful analysis, as usual. There are probably two things worth considering here. First is how much of the switch made by artists like Adekunle Gold, from "folksy to urbane cool" as you put it, was instigated by the need to appeal to a global audience at a time when the algorithmic pull of amapiano was not yet available. Juls and Mr. Eazi are significant touchstones for that change, as you suggest here, especially for how they offered a danceable low-bpm (Ghanaian) style that could travel globally as an alternative to juju. The second detail worth probing is the rise of social media sites where the virality of dances merged with the market demand for global stars. This is the part of Kizz Daniel's transformation that requires even more analysis. We may not yet have access to the numbers, but it is not insignificant that with Buga a usually niche Kizz Daniel found audience beyond his usual Juju-oriented crowd, even if they were not always dancing with him.

Brilliant review. I love the insightful dig into the past.