It is one of those starless Friday nights in Lagos, Nigeria. Traffic is at its peak. Commuters rush homeward, to the mainland, to their loved ones. Revelers head in the opposite direction, to the island, searching for a star illuminated by stage floodlights.

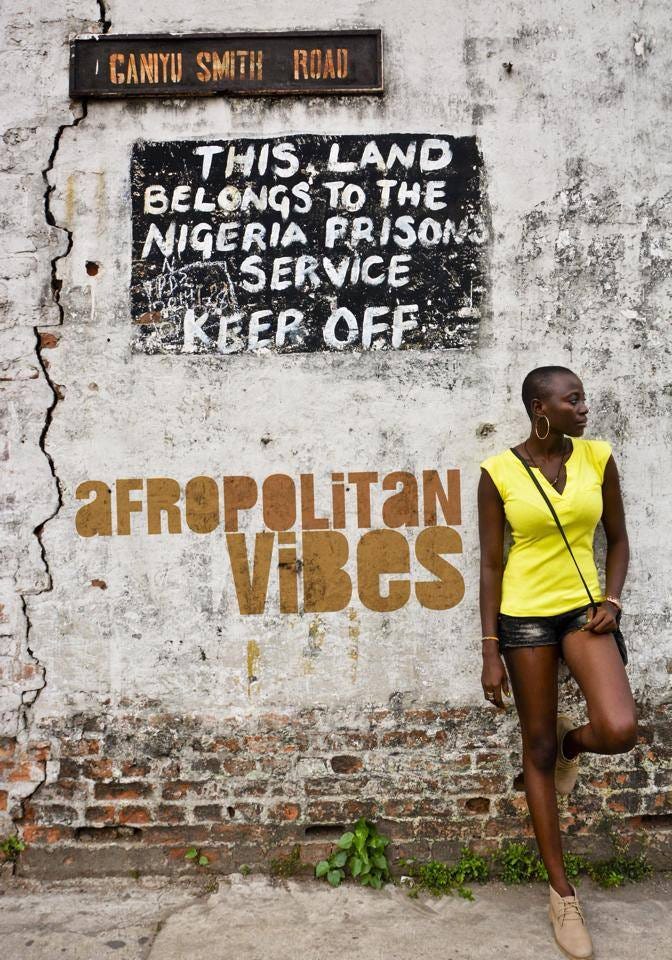

The venue is on Lagos Island, a colonial prison liberated from its manacled history as a park themed around freedom, appropriately named Freedom Park. The former prison grounds have been transformed from within but retain their imposing perimeter fence. Tucked away on the Broad Street aspect of the Freedom Park is an Amphitheatre throbbing with bodies gyrating to live music.

The year is 2015. The show is Afropolitan Vibes, a monthly concert series helmed by the 13-piece band Bantu. A lanky young man named Burna Boy leads the band, performing his latest single, ‘Soke’, a mid-tempo jubilatory song about the euphoria money brings. The music borrows heavily from two Fela Anikulapo-Kuti songs, ‘Lady’ and ‘Army Arrangement.’ It adapts easily to the live format, with the brass section piercing the night with their horns.

Suddenly, there is silence.

A power failure has occurred. The beam from the stage floodlights dies. The microphones are dead. All of the music produced by electricity-powered equipment ceases. What remains of the music: the drummer thumping away at his kit, distant without sound amplification, technology’s ferry.

But the music continues. Burna Boy continues performing, unperturbed; hundreds of phone lights trail him. The dancing and singing continue. The audience seems more concerned than the band about the power outage, a normalised experience in a country riven with erratic power supply.

Power returns within seconds and that glitch is quickly forgotten by the audience. I am a part of that audience, a resident doctor at the psychiatric hospital in Yaba, Lagos mainland. A frequent attendee of this concert series, I am one of those revellers who travelled across the Third Mainland Bridge for this concert headlined by Burna Boy.

I had written a short profile of Burna Boy for the accompanying magazine, shared freely on the concert grounds. In the intense heat of the night, the magazine serves a more immediate purpose as a hand fan for revellers.

I am in awe of this musician’s stagecraft; it is nothing like I have seen from his peers, who have yet to headline Afropolitan Vibes. In retrospect, Afropolitan Vibes was frequented by bougie Lagosians, mostly middle-class professionals and Diaspora returnees, who identified as Afropolitans, a generation of African emigrants that Nigerian-Ghanaian author Taiye Selasi eloquently described in her influential 2005 essay, “Bye-Bye Babar”.

10 years later, that cohort of upwardly mobile and highly skilled Africans has returned ‘home’, occasioning a surge in culture-related activities. Afropolitan Vibes was just one of them and by far the most important to music.

In 2015, Olamide was arguably the biggest musician in Lagos. His annual concert series, Olamide Live in Concert (OLIC), is held in a 5,000-capacity hall at Eko Hotel. Accountants and artisans alike occupy different tiers of access to the pier-shaped stage. A horde of touts surrounds the hotel grounds, selling fake tickets at exorbitant prices. Undoubtedly, Olamide was more popular than Burna Boy in 2015. Although Burna Boy was not yet at the height of his powers, he could fill the 500-capacity amphitheatre at Freedom Park.

2015 was an interesting year for Burna Boy. His sophomore album, On a Spaceship, released by his recently floated indie record label, Spaceship Records, was a unanimous sophomore slump. It paled behind his solid debut album, Leaving an Impact for Eternity (L.I.F.E). In retrospect, L.I.F.E was sonically ahead of its time, as much as Burna Boy’s achievement as it is his producer Leriq.

Cultural Critic Oris Aigbokhaevbolo’s review of On a Spaceship noted, “the unevenness of Burna Boy's sophomore may be due to the absence of the Burna Boy-Leriq partnership…” but there were more organisational deficits at play. Burna Boy had exited Aristokrat Records at the expiration of his two-year contract. He also briefly sacked his mother as his manager.

Perhaps On a Spaceship was an apt metaphor for his state of mind. He was physically and metaphorically isolated. He had misread the snobbery from the awards committee as commentary on the quality of his music and made an album preoccupied with this rejection. There were the exceptional sonic earworms, like ‘Soke,’ which has raked in a whopping 17 million plays on YouTube Music. It was the highlight of that edition of the Afropolitan Vibes concert and a sign of what was to come.

“Damini Ogulu was born in Port Harcourt on 2nd July 1991 to Bosede and Samuel Ogulu as the only son and eldest of three children”, reads the press kit I received to compose Burna Boy’s profile for the Afropolitan Vibes Magazine. The next sentence reads, “Coming from a family where music was loved but where [a] greater premium was placed on education.”

I suspect someone close to Burna Boy wrote this striking quip, a caveat that renders Burna Boy an iconoclast within his family. Perhaps his mother, Bosede Ogulu, did. Bosede Ogulu is the daughter of Benson Idonije, Nigeria’s foremost music journalist and broadcaster. Idonije was also the first manager of Nigeria’s greatest musician, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti. In his memoir, This Fela Sef, Idonije met Fela one Thursday night in the 60s at the Broadcasting House when Fela drove down to Ikoyi during his programme, NBC Jazz Club. Fela would later work at the same Broadcasting House, but that is another story.

Idonije managed Fela’s band, Koola Lobitos. Koola Lobitos played a fusion of highlife jazz that received more consternation than enthusiasm from the general public. This was before the famous life-changing 1969 tour to America set Fela’s career on a distinct path towards Afrobeat.

While managing Fela, Idonije continued his journalism career, writing a regular column about music in national dailies. In the 90s, he was an elder statesman of journalism and a respected jazz aficionado. Idonije’s writing was particularly preoccupied with American jazz of the Bebop and Hard Bop era. Occasionally, he would write about the local music scene, elaborating on ethnic genres like Highlife, Juju, and Sakara, but with far less enthusiasm than he reserved for Jazz. At home, his teenage grandson, Damini, was listening to his records with him. Damini’s mother noticed her son’s aptitude and gift for music, as well as his precocious love for performance.

Damini’s early life and love for music mirror Fela’s. Like Fela, Damini had an insatiable love for music. He founded and led a band, “DEF Code”, in his high school days at Corona Secondary School. Like Fela, he studied in the United Kingdom, although Burna Boy did not study music. He studied Media Technology at the University of Sussex from 2008 to 2009 and then continued his studies in Media Communications and Culture at Oxford Brookes University from 2009 to 2010. While in the United Kingdom, he was allegedly arrested and jailed for his involvement with gangs. This aspect of his past is understandably exempted from the press kit. Burna Boy returned to Nigeria before completing his studies. He did a one-year internship with Rhythm 93.7 FM Port Harcourt. He alluded to this dark period of his life in songs like ‘Freedom Freestyle’ and ‘Pree Me’.

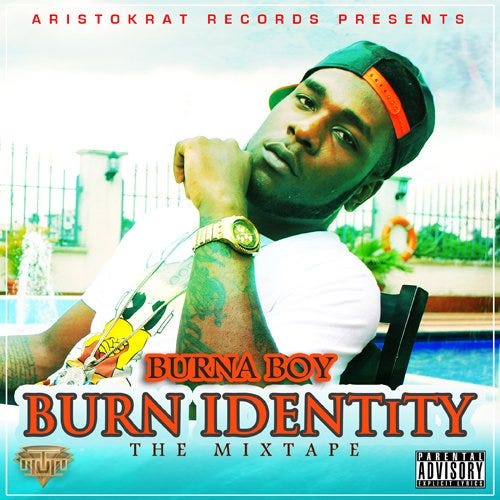

Burna Boy signed to Aristokrat Records shortly after his return to Nigeria. In April 2011, he released Burn Notice Tha Mixtape, an 11-track record with production credits by Leriq on 10 tracks. Six months later, Burn Identity, a 15-track mixtape, was released. Whilst Burn Notice had no features, Burn Identity featured established stars like Shank and Saucekid and emerging stars like Davido, LOS, and PRE.

Both mixtapes were marketed as prequels to his debut album and did a decent job of creating some buzz. If the Hollywood spy film franchise Bourne series provided record titles, the mixtape jackets borrowed their visual vocabulary from low-budget Nollywood home video promotional posters. The music, however, stayed faithful to the gritty and playful format of mixtapes. Music was sampled and interpolated from an archive of Black Diaspora genres like Reggae, Afrobeat, Hip-Hop and R&B. With Leriq’s production values reminiscent of American producer Timbaland and Burna Boy running a marathon around music genres with unalloyed joy and confidence that belies his age, these mixtapes exude immense talent and reverence for musical traditions.

More than a decade after their release, these mixtapes highlight Burna Boy’s precocious gift and prescience. In 2011, the contemporary music landscape in Nigeria was in flux. While Burna Boy sizzled creatively on the fringes of the Port Harcourt musicscape, Timaya and Duncan Mighty were at the height of their powers, milking a dancehall style inflected with their native rhythms around the oil-rich Southern region of Nigeria for which Port Harcourt was the most cosmopolitan city.

Ranked the fifth largest city in Nigeria and named after Lewis Harcourt, a paedophile and British politician, Port Harcourt is economically prosperous and a magnet for oil expatriates and local contractors. Consequently, Port Harcourt's vibrant nightlife relied on high-quality music and performances. In 2011, Timaya and Duncan Mighty were the most sought-after musicians in that region. In Lagos, southwest Nigeria, D’Banj and dynamic duo P-Square were the biggest stars of Afrobeats. Confident in their hold on their local fanbase, these musicians sought international recognition by featuring American rappers Snoop Dogg and Rick Ross in their latest tunes. Rappers heavily influenced by American hip-hop, such as Naeto C, MI Abaga, and Ice Prince, were also at the height of their powers, enjoying the swansong period of American influence on Afrobeats.

Peers Olamide and Wizkid released their debut albums, Rapsodi and Superstar, respectively. Both albums announced the arrival of two talents who have now ascended into superstardom, but in 2011, they were creative upstarts in Lagos—and Burna Boy was in Port Harcourt, 442 kilometres away.

Aristokrat Records released Burna Boy’s debut album, Leaving an Impact for Eternity, in 2013. Stylised as L.I.F.E and comprising 19 tracks, it opens with his grandfather’s comments on his music, highlighting that it is Hip-Hop but with strong influences of jazz, Highlife and Juju. Featuring emerging and established stars like 2Baba, Timaya, MI Abaga and Reminisce, L.I.F.E sold 40,000 units in its first week of release.

Streaming was not the mainstay of music consumption in Nigeria in 2013. Typically, highly sought-after musicians sold their marketing rights to a designated distributor (read pirates who would have pirated their music regardless) who paid them a hefty advance. Aristokrat Records received 10 million naira (approximately 65,000 dollars in 2013) for L.I.F.E.

The album’s standout moment was the mid-tempo and groovy party starter, ‘Like to Party’. It is nothing like you have heard. Overdubbed, wobbly chords matched with staccato percussion were held together by Burna Boy’s patois lyrics. The song opens, “You see my dark shades on/and I can see you/and you know me fancy you”. And there is more: his flow has the texture of dancehall toasting but the cadence of slow rap—and instead of one hook, ‘Like to Party’ features two layered hooks.

Hardly straying from influences of R&B, reggae, dancehall, highlife and hip-hop, Burna Boy was unsurprisingly more confident and accomplished on songs without assistance from featured musicians. Entirely produced by Leriq and supported by other singles, "Tonight", "Run My Race", and "Yawa Dey", L.I.F.E was well-received among listeners with similar backgrounds: middle-class to affluent families, private school educated. To put it simply, emerging Afropolitans.

L.I.F.E was nominated for Best R&B/Pop Album and Album of the Year at The Headies Awards but lost in both categories to Sean Tizzle’s The Journey and Olamide’s Baddest Guy Ever Liveth, respectively. It was Burna Boy’s second time losing in a category at The Headies to Sean Tizzle, who clinched the coveted Next Rated award at The Headies Awards in 2013.

The Headies Award for the Next Rated is given to the “most promising upcoming act in the year under review.” Determined by voting consensus open to the general public, it provides a snapshot of its voters, the Nigerian public. It was awarded to Wizkid and Davido in 2011 and 2012, respectively.

In retrospect, perhaps Burna Boy was a sore loser for whom nominations for these awards would not assuage his gigantic aspirations — he had to win! He knew he was special and did not belong on the fringes or in the cohort of nominees. This preoccupation filtered into his lyrics, alongside his constant acknowledgement of the critics’ commentaries. His sophomore LP album, like his first, opens with music journalist Osagie Alonge’s commentary on Burna Boy’s dissocial behaviour and his frequent brushes with the press and bloggers.

Burna Boy made two important career decisions: He reinstated his mother as his manager and returned to the studio with producer Leriq. In 2016, he released new music, an aptly titled 7-track EP called Redemption.

Burna Boy’s Redemption retraces his steps from his spaceship voyage misadventure back to his stomping ground. Lasting about 20 minutes, it is a return to vintage Burna, that playful, experimental Burna Boy of the Burn mixtape series. He experiments with sound but from the secure base of his strengths. To reiterate, his strength lies in his musical pedigree, which is at risk of being overexposed.

On the most vulnerable track of the record, ‘Pree Me’, Burna Boy addresses the hoopla of an artistic career. He sings, “I have a lot of enemies/some of them used to be my friends. But the general attitude of the song is that of watchful waiting, of relentless continuance.

It brings to a full circle the brief incident of power failure at the Afropolitan Vibes concert and his unperturbed handling of a moment that could have otherwise ruined his set. That perfect moment became a metaphor for his resilience, an understanding of his place in the annals of contemporary West African dance music. He knew he was bidding his time; little wonder he sings on ‘Anybody’, “I bin dey answer dem yes sir/now na me dem dey answer yes sir.”

He knew his time was coming, in the same way, Reggae legend Bob Marley emphatically knew that the stone the builder refused would become the cornerstone.

You did justice to this piece as usual.

L.I.F.E was perhaps way ahead of its time and unnecessarily always underrated

This was such a good read❤️