Naming love songs after girls is the gift that keeps giving.

The old timers—highlifers and Juju exponents—knew this.

Mention a girl’s name on wax, sing sonorously about her geographical location, croon in the same breath that you have dispatched yourself in her direction—and you are half-way to her heart.

Taxi drivers were a regular fixture in highlife love songs in the 1960s, when vehicular transport was a miracle. Since advanced technology was introduced in web 2.0, social media apps, instant messaging, and emoticons, Nigerian music has responded appropriately. Essence and Jaywon’s Facebook Love set the tone for communicating affection in song with a new vocabulary for loving.

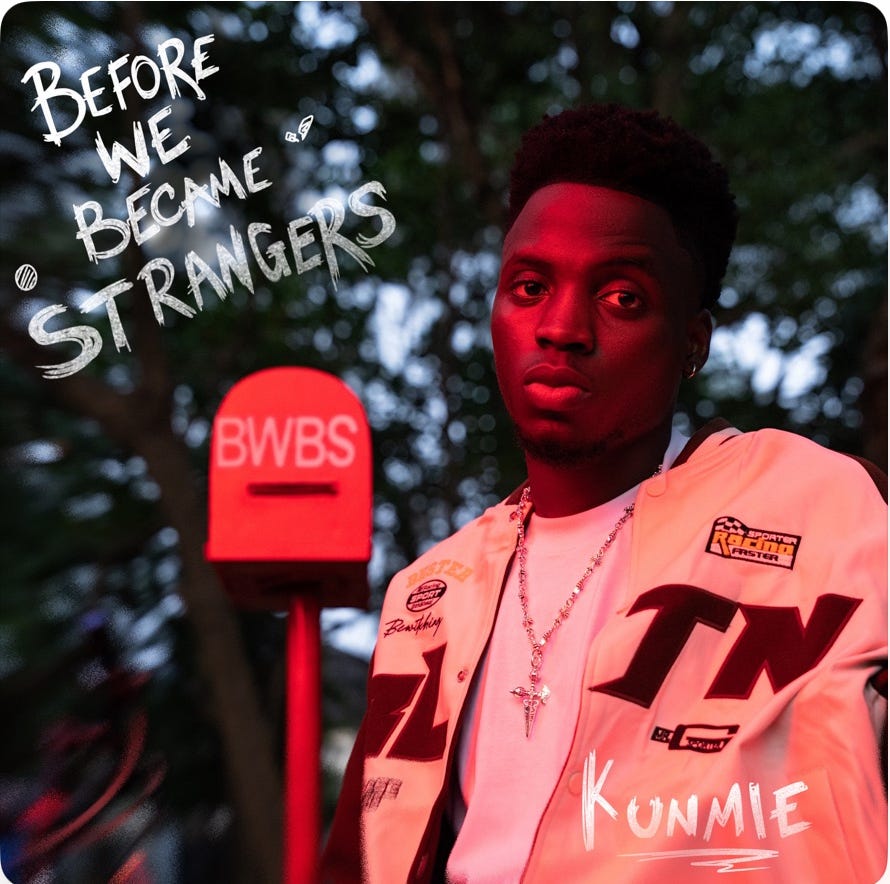

Newcomer Kunmie begins his debut EP, Before We Became Strangers, with a voice note. It is a female voice, a nervous chuckle. Someone is being vulnerable in a voice note: a one-sided missive sent in a cyber bottle without the certainty of a response.

Kunmie sings his incarnation of Avant’s Right Place, Wrong Time. It is less singing and more crooning, with his verses more dancehall than R&B. He channels Ruger but is more introspective, without a shred of misogyny but selfish no less. It is an exteriorising of demons and dysphoria, things that hamper with commitment. The chorus defers closure: "Good Girl want you far away from me/If I see you again, I will tell you my reasons."

Perspective is flipped on Majekaja, gently propelled by rhythmic talking drums. The music is busy but spatial. All in service of a swain’s proposition. Kunmie’s hook, adapted from Yoruba folk music, sues for peace. A love interest is pissed. Kunmie’s verses are reconciliatory and work because he relies on the sonic instincts of contemporary forebears like Adekunle Gold. Ten years ago, Adekunle Gold scorched our hearts with his perfect blend of Yoruba rhythms charged with Lagos colloquialisms, Kunmie toes this overgrown path Gold abandoned for Afropop flamboyance.

Arike is the EP’s gem. Arike is a Yoruba name. According to the website Yoruba Names, it means one that is cared for on sight. I suspect this translation is inadequate. Perhaps Kunmie agrees with me, so he deconstructs Arike to its syllables as part of his Yoruba chorus.

What is better than one hook? Two hooks intertwined and converging with superimposed meaning, all in service of Arike, or more pointedly, Kunmie’s undisputed affection for her. Of all the songs on this record, Arike is the most uncomplicated in its messaging. This lover will die before his time, if Arike does not return from her beauty sleep. The fear of abandonment cannot be more existential!

The final song, One More Chance, might be EP’s weakest chain. Done entirely in plain spoken English and rhetoric, the song writing here is chaotic, saved by a strong vocal performance, perhaps his strongest on the EP. The brief is similar to EP’s spirit. It is a forlorn love song about owning up to missteps, propositioning second chances. There is a fascination with weather and the sun. The sun sets on a lover’s skin. In the same vein, love does not die because feelings are real. These are the kind of clichés writing in Yoruba and Pidgin English save you from. To end the record on a lull, is the kind of misstep Before We Became Strangers should have avoided.

An EP is small chops, for the lack of a better Nigerian metaphor. The packaging, songs, and complimentary toothpick must serve a listener’s experience, a foolproof introduction. Kunmie’s Arike stands tall as a strong single, but Before We Became Strangers—I know, mouthful and fuzzy title—hardly rises to the occasion.

We don’t come away with a strong sense of Kunmie’s style as a crooner. Take Ayo Maff, for instance. His messaging, cadence, and abiding bromance are all in service of a sound that ferries Tope Alabi’s gospel straight into Gen-Z Street-Hop. Kunmie is not served by a reedy voice like Buju or a facility for cantillation like Seyi Vibez. He writes and sing songs with a tender touch. Time will tell if this is enough.