64. Why Does a 30-plus Man Have an Unusual Taste for Highlife?

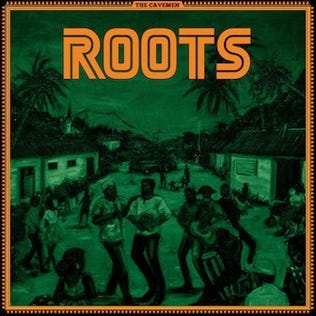

Revisiting the seminal classic album, Roots

A working man’s weekend is sacred.

Every 9 to 5 man who leans too deeply into the arts learns the restraint and pragmatism of that counsel ringing from childhood: stay in school, stay off drugs.

But staying in school and off drugs does not kill the affliction of the incessant earworm. There is a tune in my head every time. Sometimes, this rhythm betrays my most well-meaning intentions in the most inappropriate places. This rhythm assures me I would have been a songwriter in another life. But I am a psychiatrist. Fancy consulting with a patient and then a phrase from The Cavemen.’s Bena leaps to the tip of your tongue. You must swallow uncomfortably.

This is why the weekend is sacred. On Sundays, I open the carcass of my vinyl player and play my modest vinyl collection.

Since Bena's near-miss happened on a Thursday, I should listen to Roots this weekend to treat this affliction. But The Cavemen. have yet to provide their dazzling debut record in vinyl. That refusal undermines the total experience of nostalgia promised on Roots, but this is neither the time nor place to dwell on privileges. This highlife fiend needs his fix.

Why does a 30-plus man have an unusual taste for highlife, a genre already moribund in the 80s when he was born? Now consider that I fell for highlife at least a decade ago. I was a medical student in my 20s when my love for Fela led me down this rabbit hole of music reminiscent of an era when I did not exist.

There is a collective unconscious. There is an optimism trapped behind timelines framed by this music that fills my heart with pride, my blood vessels with endorphins, my cerebral cortex with euphoria. I cannot explain it. My friends have diagnosed me as an old soul.

When Roots came out in 2019, it felt like an ethereal listening experience. It still is. I don’t understand how it happened; how two brothers at least a decade younger than me can produce timeless Igbo heartland highlife. These lads were born in Lagos, Southwest Nigeria and the verdict of some Igbo speakers is that their Igbo is faulty. But when you listen to the music, it transcends language. It amplifies mood.

In his seminal review of Roots, IfeOluwa Nihinlola writes, “The boys that make up The Cavemen. are calcified in my mind as wide-grinning, energetic, and possessing of a personal style — loose linen and plaid dresses in earthy colours — that projects an ease many stumble through life trying to find.” There is the younger, dark-skinned, and muscular Benjamin James, a spirited drummer gifted with an ululating falsetto. Older Kingsley Okorie appears moody. He strums the bass guitar as if plucking wisdom. The two are The Cavemen. The Cave, of course, is a metaphor.

On the opening track, Welcome to the Cave, a question is asked and answered in a mocking Nollywoodsque monologue.

“What is the Cave?”

“The Cave is the heart of a man.”

These notions of visceral masculinity contrast their music’s message. In their defence, their framing of the Cave as a metaphor is fluid. The Cave is the dancehall that Highlife inhabits. The dancehall was once the colonial ballroom. At the same time, the Cave is primordial, pre-colonial. The conceit is that foreign musical instruments score a pre-colonial African expression. The Cave is dark and ought to be gloomy.

The trauma of the Biafra War is yet to be reflected upon through music. This will happen in due course. And when it is done, the music will be highlife. A simplistic examination of highlife music is to say that when the Igbos fled Lagos (read Nigeria), they took Highlife with them. There is evidence of the rise of Juju music in Lagos during the War. During the Biafran war, Rex Lawson sold salt.

Although Highlife’s immediate post-colonial optimism was short-lived in its purpose, it has persisted in making this music about escapism. War is a terrible thing. Memory is tempered by what the mind can withstand. Memory shirks from grief and dials back to love.

Roots is replete with love songs named after lovers. Bena fits the femme fatale archetype. Anita is so gorgeous that she attracts a marriage proposal. Ifeoma Odoo reduces a man to tears. In this way, Roots fits directly into the 60s Highlife canon of songs that derive their name from women. Eddie Okonta’s Bisi, Orlando Julius’s Jagua Nana. Roy Chicago’s Maria. Rex Lawson’s Hannah.

Did Celestine Ukwu name a song after a woman? The Cavemen.’s Osondu is similar in text to Celestine Ukwu’s Usondu. There is a deeper layer of similarity which Tunji Olalere, in his poetic review, described as “a motif of melody”. That motif is vocal in Ukwu’s philosophical tune; on Osondu, it is pure metallic guitar.

When I arrive at this song, it feels like a full circle. It was their debut single and I return to it as the penultimate song on Roots. It remains flaming hot, pensive, tentative. This is precisely what I needed to cure the rhythm in my head, to be etherised by a motif of melody on a wintry Sunday afternoon in February.

Bro… I’m Zimbabwean. My Spotify shuffled me to The Caveman and my life was never the same. There was something familiar about that sound and the nostalgia it brought although foreign to me.

It’s tribal, soulful, spiritual and just different. One of my favorite artists from West Africa.

Great piece.

Roots is truly a phenomenal album!