“Learning about Fela was an experience in itself, and one that I would not have missed for anything.”

A few pages into the recently published posthumous memoir Mrs. Kuti, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti’s first wife Mrs Remilekun Jean Ayodele Anikulapo-Kuti, affirmed her belief in zodiac signs.

Born on July 12, 1941, in Maidenhead, England, her sign was cancer. True to her sign, she was introverted, moody, and supportive. Born on October 15, the love of her life, Olufela Ransome-Kuti, whose star sign was Libra, was outgoing, charming and strived for justice and fairness for all. Their zodiac signs were compatible on paper.

Their twenty-two-year-long relationship began in the summer of 1959 at a house party in London, where a shabbily dressed Fela approached her for a dance. She was 18. He was 21. She told him she could not dance. He offered to teach her. She gave in to his request. While dancing, he asked her to be his girlfriend. She disclosed her age, partly to rebuff his advances, but the charming devil applied pressure.

I wish this meet-cute had progressed into a happy ending with an American-style nuclear-sized family, the type perpetuated by romantic comedies, but you already know this—it didn’t!

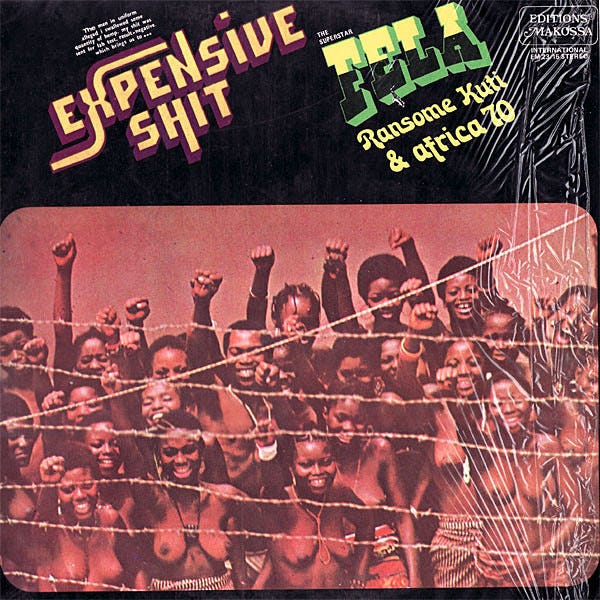

On February 20, 1978, her estranged husband married 27 women at once. In her memoir, Mrs Kuti stated that Fela did not disclose his intention to desecrate their marital vows taken in London seventeen years earlier. Instead, he sent an emissary. Fela, who initiated this grand spectacle of polygamy, which scandalised the largely conservative Nigerian society, could not directly inform his wife of his intentions. This contrasts with the mythical Fela, whose innovation, Afrobeat, annexed dance grooves and sarcasm in the service of activism. With this Afrobeat music, Fela poked the eye of the ruling class, daring them with his actions, including residing (and presiding) in a commune, the Kalakuta Republic. He could face up to the government of the day but outsourced difficult conversations with his wife.

Suffice it to say that Mrs Kuti’s memoir reveals a different Fela. It is an intimate portrait of a devoted man. A thoughtful lover who cooked meals, revered his mother and older siblings, was chummy with his mother-in-law, and doted on his children. Their marriage was an unconventional one with a clear sense of partnership.

After they met at the house party, she declined Fela’s proposition to be his girlfriend, but his charm never left her. One may say that she pined for the man. Her wish to see him again materialised at a lavish birthday party five months after the meet-cute. His band, Highlife Rakers, was hired to perform at the Nigerian High Commission in London. They will be married one year later, precisely to the date.

Mrs Kuti's remarks on Fela’s actual songs are few. We are not told about the songs his band, Highlife Rakers, played at the birthday party. We may guess that their set included songs like Fela’s take on Victor Olaiya’s ‘Ai Ga Na’ and ‘Fela’s Special’, both songs recently resurfaced in an anthology of old tunes. However, Mrs Kuti told us that Fela’s beautiful tenor was damaged by playing the trumpet. She told us that Fela nurtured his band members who betrayed his affection.

Mrs Kuti regarded Fela’s early music as Jazz. The first time Afrobeat is mentioned was in reference to Fela’s monkey, Afrobeat. These are the surprising ways this memoir rewards with intimate nuggets. The Fela Stan probably knows little about Fela, the zoophilist who also nurtured a cat and a donkey and owned an Alsatian. Or Fela, the messy eater, who smeared his fur coats with food debris. We know of his extraordinary generosity but know little about the devastating consequences, particularly for his immediate nuclear family.

Mrs Kuti identifies ‘Buy Africa’ as one of the first tunes to portray the struggles of Black Africa. There is no mention of ‘My Lady’s Frustration’, the opening tune of Fela’s controversial album LA 69 Sessions, which was explained by Fela (to Benson Idonije) as a tribute to Sandra. Idonije, Fela’s first manager and author of a memoir, Dis Fela Sef, identified ‘My Lady’s Frustration’ as Fela’s first song with “an Africanised approach”—whatever that means.

Of course, these myths pale compared to the material deprivation Mrs Kuti suffered in her husband’s absence those nine long months when Fela and his Koola Lobitos band toured the United States. She dealt with the irresponsible behaviour of telephone operators eavesdropping on her conversations with him, the irresponsible press that published fake news that Fela was jailed for raping a 12-year-old, and Fela’s dubious friend in charge of his club Afro-Spot (formerly Kakadu) who mismanaged its earnings.

Mrs Kuti was a traditional woman. She believed that the husband provides. Her family rationed their limited resources while Fela prospected for a fortune after they left England for Lagos. This deprivation worsened in 1969. Mrs Kuti and her kids thrived on crumbs in Lagos, while in Los Angeles, Fela lived with his lover Sandra Izsadore, taking a crash course on Blackism.

Mrs Kuti is courteous in her examination of this crash course. In her own words, “If Sandra Daniel had anything to do with Fela’s change, she did a fine job, but I believe it was also a personal effort on his part.”

Mrs Kuti’s early life was challenging. Her mother (referred to as Mum, different from Fela’s mum, Mummy) split from her Nigerian lawyer father when she was young. Mum left Lagos for England with Mrs Kuti and younger sister Sonia. Both girls were soon separated from their mother on account of Mum’s ill health; they grew up in foster homes enduring physical and emotional abuse aggravated by racism and colourism.

Such adverse childhood experiences predict future outcomes. Consequently, despite spending her formative years there, Mrs Kuti never saw England as her home. Once she married Fela and started her family, she was eager to return to Nigeria, where she lived until her death on January 12, 2022.

Fela’s return from America brought fame and material success. During his time away, he perfected Afrobeats, a fusion of musical traditions superior to the sum of its parts. Fela moved away from tame and inconsequential love songs toward social commentary with overt political messages. He soon ran into trouble with the political class of military rulers deploying state-sanctioned violence at will.

Mrs Kuti shared a profound insight as to why the Nigerian military scapegoated Fela and his commune. In her reasoning, it was a direct consequence of conscripting unsavoury elements into the army during the Nigerian Civil/Biafran War. After the war, they remained within the ranks of the military disproportionately empowered, abusing their license to brutalise civilians.

“My main emotion at that time was a deep, dangerous anger, but I was determined not to show my feelings to anyone; to show only strength instead. But when a man passed me in uniform all my lectures to the boy were forgotten.”

Although this memoir avoids explicit political discussion, it examines the subtle impacts of political action. Mrs Kuti and her family were on vacation in Ghana when Nigeria expelled Ghanaians after the Ghana Must Go decree. They faced hostility from the previously friendly hotel staff in Accra until the staff learned they were Fela’s family.

Mrs Kuti also had much to say about Fela headlining the Berlin Jazz Festival in 1978. This festival is of extraordinary importance to Fela lore and has received short shrift. For instance, she shared her account of the bitter rivalry between Fela and Ginger Baker, billed to perform alongside Fela at the Festival.

“...Fela tended to let old friendships slide when new ones came and unfortunately, Allen allowed jealousy to consume him, so he could not think straight where Fela was concerned. Fela did not mind criticism if it was sound, but Allen’s story reeked of sour grapes.”

The Berlin Jazz Festival is seen as the peak of Fela’s career. Indeed, it was a period of enormous pressure. The year before, the most brutal army sacking of Kalakuta had occurred. Fela’s body was broken, but his resolve was thoroughgoing. Fela, the perfectionist, made several mistakes during his set, but Mrs Kuti, watching the concert live, was incredibly proud of her husband.

Afrika 70 band did not survive the Berlin Jazz Festival. It was the last straw that led master drummer Tony Allen to quit the band and perhaps one of the most creative collaborations of the 20th century. Mrs. Kuti was critical of Allen, who, in turn, was critical of Fela in his autobiography written with Michael Veal. In her opinion, Allen was jealous of Fela’s success. In Allen’s biography, there is a sense that he saw himself as Fela’s equal. In Mrs Kuti’s opinion and with receipts, too, Fela risked it all for his band, placing the welfare of his band members above his family.

These different accounts of the same event enrich us with multiple perspectives. At present, the welfare of musicians playing in bands is the stuff of public debate in Nigeria. Bandleaders, living and dead, are being scrutinised. Mrs Kuti’s memoir provides an insight that diminishes some of my sympathies for members of the Afrika 70 particularly Tony Allen.

“…in one of our wedding pictures, his eyes showed up red and he held his handkerchief ready for action. He said he was crying because he did not want to get married. He was joking, of course. If I thought for one moment he meant it, I would have given him a good punch.”

Mrs Kuti’s anger towards Fela waxed and waned. Her frustration was often communicated through assaultive fantasies, which eventually culminated in her striking Fela across the face once. He retaliated.

In her opinion, Fela was not a violent man. She believed he struck her because she slapped his face. He obsessively protected his lips—the most prized organ of a horn player.

Mrs Kuti wrote moving love poems. An introverted person, it was not unusual that she consigned ambiguous thoughts about Fela to verse. In ‘My Dream in 1973’, she wrote, “My lover is having himself a ball/leaving me always, always alone”. Unsurprisingly, she almost filed for a divorce around this time. In ‘My Dream in 1979’, she wrote prophetically about her husband’s legacy, “His music, his works and his fame/Are given for those yet unborn/They will not be a people shamed.”

Many readers will have preconceived notions about her marriage to the most forward-thinking musician Africa has ever produced, but one thing is clear from this memoir: She wasn’t a pushover. She was an equal partner in the Afrobeat legacy, the mother of his three children, and a defiant keeper of his quiet moments.

Ah you beat me to this! I can’t wait to read the book. Lovely critique. I would love for Dede, Lemi and Baba Ani to write books on Fela. The more stories and narratives will help us get a realistic picture of the enigma.

Such a beautiful review. Now I have to get a copy to learn more about this amazing woman, and to understand Fela from her perspective.

As always, thank you for writing.